Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm

Imperial War Museum

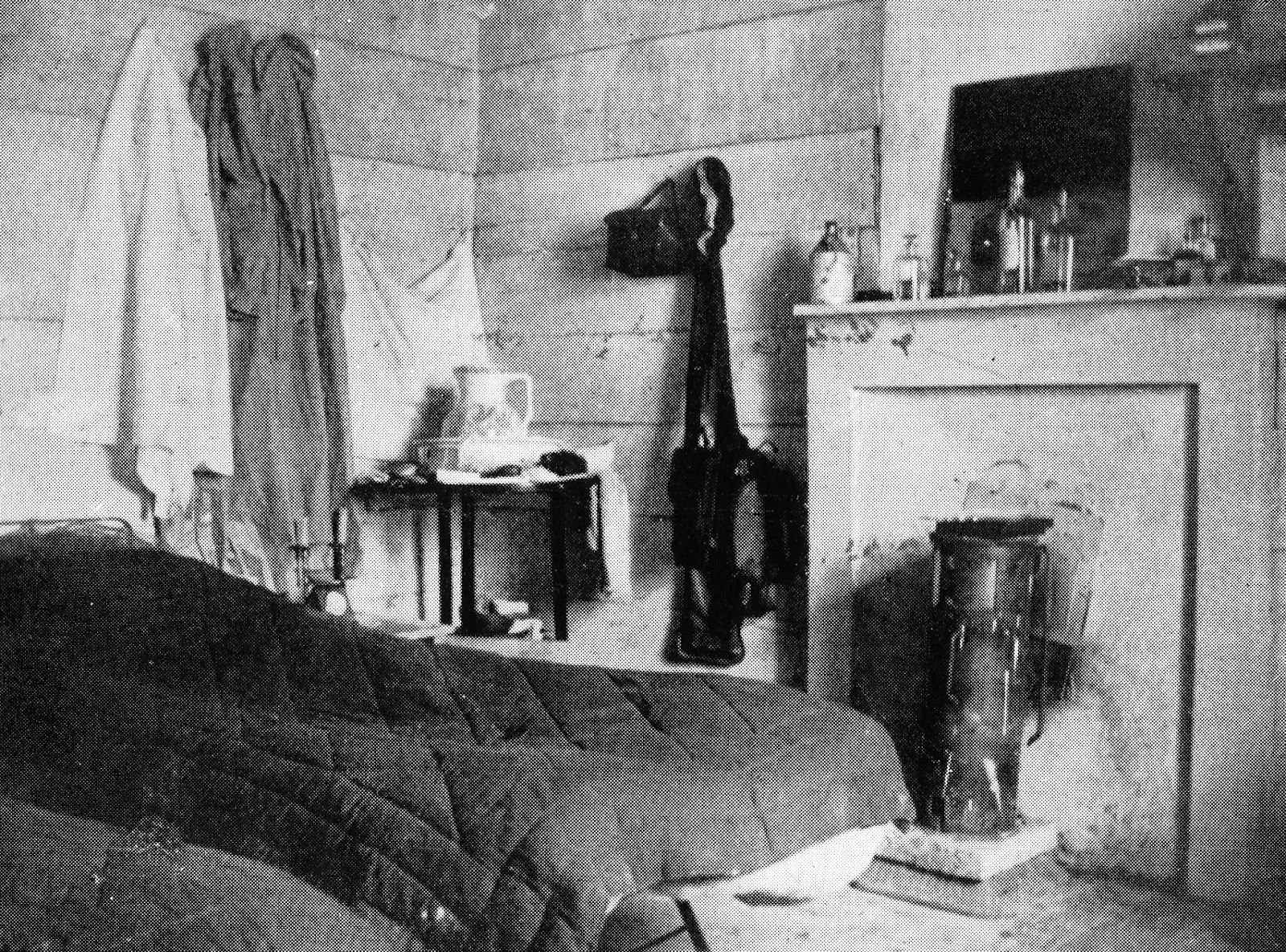

Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm were two motorcycle enthusiasts who, when the war began, worked as dispatch riders in London for a month before being chosen to travel to Belgium with a unit called the Flying Ambulance Corps. When they noticed that even moderately wounded Belgian men were dying of shock during the long ambulance rides to the hospital, the women decided to create a relief station close to the fighting where these men could recuperate before making the trip. Knocker and Chisholm were both personally decorated by King Albert of the Belgians for their efforts.

Read more about Knocker and Chisholm here.

Elsie Inglis

Elsie Inglis was a Scottish surgeon who offered her services to the British War Office when the war began. She was turned down with the following words: "My good lady, go home and sit still." Inglis did neither. With funds raised by the Scottish Federation of Women's Suffrage Societies, she created the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service, mobile units staffed and run by women that were utilized in France, Serbia, Salonika, Romania, Malta, Corsica and Russia. Inglis spent much of her time in Serbia where, because of her efforts, she became a national hero.

Radiographers Helena Gleichen and Nina Hollings at work

Helena Gleichen and Nina Hollings were two British women who worked as radiographers on the Italian Front, locating pieces of shrapnel and bullets with their equipment so that surgeons could operate on wounded men more precisely. Often coming under fire, both women were decorated by the governments of Italy and Britain.

Read more about Gleichen and Hollings here.

Olive King with her ambulance.

Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial

Olive King was the daughter of a wealthy Australian philanthropist who provided his daughter with funds for a truck which she converted to an ambulance. She worked with the Scottish Women's Hospitals in France and Serbia before attaching herself to the Serbian army. When a fire broke out in Salonika, Olive worked to rescue people from their burning homes, for which the Serbian government awarded her the Silver Medal for Bravery and a Gold Medal for Zealous Conduct. Towards the end of the war she opened canteens for the Serbs as they pushed their enemies out of their devastated country.